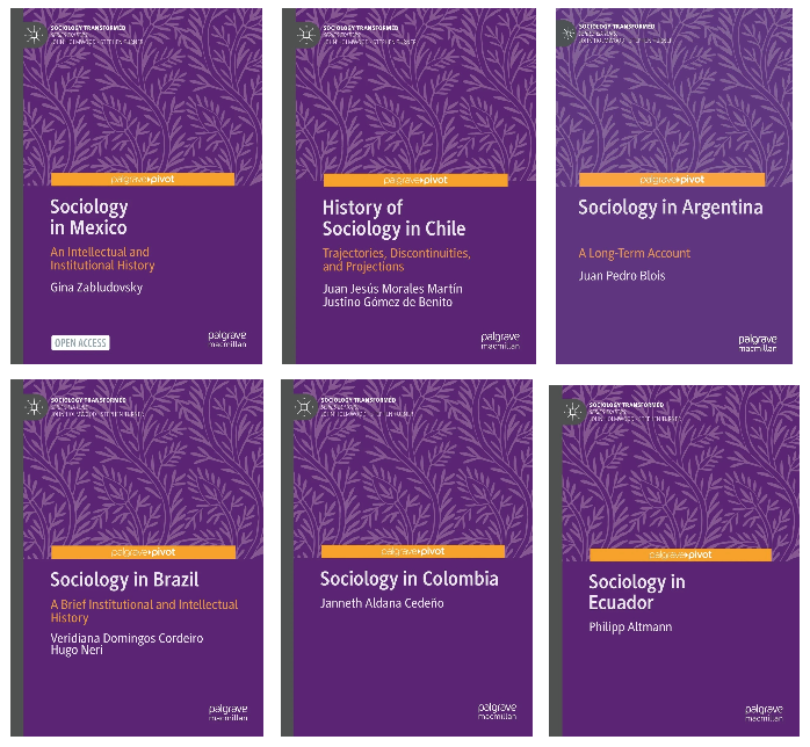

Book series Sociology Transformed

Book series Sociology Transformed

Series Editor John Holmwood & Stephen Turner

Palgrave Macmillan

About this book series

The field of sociology has changed rapidly over the last few decades. Sociology Transformed seeks to map these changes on a country by country basis and to contribute to the discussion of the future of the subject. The series is concerned not only with the traditional centres of the discipline, but with its many variant forms across the globe.

View all book titles>>

Sociology in Mexico

Authors: Gina Zabludovsky

Open Access

Introduction

The book presents a condensed history of sociology in Mexico from its origins in the mid-nineteenth century to the present day. Most of the research and publications on the subject has focused on a specific historical period, the contributions of a reduced number of sociologists, a specific concern, or a particular theoretical orientation. Moreover, to the extent that they are written in Spanish, most of the publications cannot be shared by academics beyond the Spanish-speaking world. This project aims to fill this gap. In comparison with the previous works concentrated on the analysis of short historical periods and a limited interpretation of history, this book will present a broader outlook and a different approach aimed at studying the constitution of sociology in Mexico in the long term. Therefore, the study provides a comprehensive account of the genesis and institutionalization of Mexican sociology and the main turning points from the mid-nineteenth century to the present.

The book presents a condensed history of sociology in Mexico from its origins in the mid-nineteenth century to the present day. Most of the research and publications on the subject has focused on a specific historical period, the contributions of a reduced number of sociologists, a specific concern, or a particular theoretical orientation. Moreover, to the extent that they are written in Spanish, most of the publications cannot be shared by academics beyond the Spanish-speaking world. This project aims to fill this gap. In comparison with the previous works concentrated on the analysis of short historical periods and a limited interpretation of history, this book will present a broader outlook and a different approach aimed at studying the constitution of sociology in Mexico in the long term. Therefore, the study provides a comprehensive account of the genesis and institutionalization of Mexican sociology and the main turning points from the mid-nineteenth century to the present.

Although the first institute of social sciences within a university was not created until 1930, since the mid-nineteenth century, sociological discourse played a fundamental role in the establishment of secular and public education, the recognition of the new role of science, and the political legitimization of the governments of the time.

The study shows how, until the mid-twentieth century, sociology in Mexico advanced in close relation to what was considered a “national project” linked to the political and intellectual interests of the ruling elites.

As sociology became institutionalized within universities, it also consolidated itself as an autonomous social science. In the 1970s, sociology was conceived rather as a critical social science against the existing political regime. Towards the end of the twentieth century, sociology in Mexico is characterized by a growing process of specialization in different thematic fields, while in the first decades of the twenty-first century, there is a tendency to an increasing interdisciplinary perspective and collective projects.

Considering the different facts that influenced the creation, consolidation, and transformation of the discipline such as the interaction with the main social movements, the relationship between universities and the government, the foundation of most important scientific journals and publishing houses, the main research institutions, the conception of sociology as a professional and academic career, and the changes in the curricula, the universities and its mains transformations, and other relevant factors for academic and professional life. The work also considers the influence of European thought, and the search for a “national and/or Latin American sociology.” From a feminist perspective, the work also studies the participation of women who have often remained invisibles in the history of sociology.

The book addresses the history of sociology in Mexico through four historical periods according to the university’s programs, the different research fields, and the main economic, political, and social changes that had a decisive influence on the development and institutionalization of sociology.

The second chapter “Sociology Precursors: From Scientific Positivism to the ‘Mexican Renaissance’” (1856–1930) addresses two different eras of Mexican history.

The first era (1856–1910) analyses the reception of the ideas of Comte and Spencer in Mexico and the importance that sociology acquired in the second part of the twenty-first century, as a discourse legitimizing science and the separation of church and state during Benito Juarez’s government (1858–1872).

The sociology of Comte was first introduced in Mexico during the 1850s, to stress the importance of science, criticize the religious manifestation across all areas of society, and defend the importance of secular and free education.

The chapter analyses the work and influence of the key authors, the role that associations with a positivist orientation played in Mexico, and the most relevant publications being circulated at the time.

In the later part of the nineteenth century, during the administration of President Porfirio Diaz (1876–1911), Spencer’s ideas, and the concepts of social Darwinism, started to grow in importance, informing the conceptual framework of the positivist discourse adopted by representatives and social thinkers of the new regime, who became known as the Scientists.

The second part of this chapter studies the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution when the incoming government adopted, as its main principles, a nationalist ideology which rejects the modernist philosophical discourse of Porfirio Diaz’s “old regime.” Since 1910, and under new influences of a group of Mexican intellectuals established the Ateneo de la Juventud, whose members opposed the positivist interpretation of history as a scientific knowledge.

This period was characterized by the promotion of cultural activities and the flourishing of the plastic arts led by the muralists, which re-created the images of the revolution onto the main public buildings. Mexico got worldwide attention and was visited by several intellectuals of different countries.

To strengthen the nationalist orientation, the new intellectual and political elites called attention to some of the social theories that privileged a conception of Mexican identity based on the racial composition, in particular the role of the indigenous groups, and the notion of the mestizos. The skepticism on the theories on modernity and the universality of progress as well the search for national expressions gave a new impulse to anthropology over sociology.

The third chapter, “The Institutionalization of the Social Sciences in Mexico,” explains sociology development from 1930 to 1959.

The first decade of this time period was characterized by the central importance of Lazaro Cardenas’ presidency (1934–1940), his innovation on policies of social equality, and his support for the immigration of Spanish republicans into the country. The second decade, that coincides, was headed by President Manuel Avila Camacho (1940–1946) and Miguel Aleman (1946–1952) who launched new policies for the industrialization of Mexico.

The anti-positivist and post-revolutionary nationalism of the 1920s and 1930s also influenced the realm of philosophy and led to an increasing importance of literature and social and political essays; some of them had to do with Mexican character and identity and would have a great influence in Mexico and the world.

Because of the Spanish Civil War, Mexico received an important number of Spanish republicans. This intellectual migration had an important cultural impact and led to the creation of two institutions of central importance to the development of social sciences in Mexico: the publishing house Fondo de Cultura Económica (FCE) and La Casa de España en México (The Spanish House in Mexico), a higher-education social science research institute which later changed its name to El Colegio de Mexico. During this time, the institution offered a degree in sociology that did not last for long.

Meanwhile, in 1930, the Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales-IISUNAM (Institute of Social Science Research) was founded at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) with the launching of the Revista Mexicana de Sociología (Mexican Journal of Sociology) which, since 1939, has been published quarterly, without interruption. Other important journals were also published at the time.

In 1955, the first Department of Social and Political Sciences was created to offer a degree of social sciences in the country that in 1966 was transformed into a sociology program.

The chapter also analyses some relevant journals and books published at this very prolific and creative period.

Chapter 4 “The Expansion of Sociology in Mexico” (1959–1980) analyses a period characterized by the widespread influence of development theory in Latin America, and by what is known as “Stabilizing Development” in Mexico, an epoch of economic growth and “social peace” which was often qualified as the Mexican Miracle. Notions of Mexico’s economy changed from what was considered as a predominantly rural country to an industrializing nation.

This time period also witnessed the creation of the publication of books written by Mexican authors that may be considered foundational for the new era of sociology in Mexico. Academics in the United States also published studies about Mexico translated into Spanish with an important impact on social sciences in Mexico.

During the end of the 1950s, there were different protest movements, led by railroad workers, medical doctors, and teachers. Together with international factors like the Cuban Revolution, they aroused a new concern for social inequality in Mexico and Latin America.

Similar to what was happening in other countries, in 1968, Mexico had an important student movement. The violent reaction of the government towards it changed the perceptions of stability and development that distinguished Mexico according to the so-called Mexican Miracle. Beyond the possibilities of industrialization and economic development, the social demands were now focused on other priorities like the struggle for freedom of speech, and a focus on a new agenda to promote democracy.

Under the new social circumstances, the decade of the 1970s was characterized by the importance of Marxism in Mexican universities, and a belief in teaching and implementing a sociology which incorporates thoughts on social reform and utopia. During this period, there is a shift in Latin American social thought, where the criticism towards the “development theory” led to the expansion of “dependency theory” and the explanation of the unequal distributions or power based in the concentration of economic and social resources in the “the centre” and the exclusion of the “the periphery.” The curricular profile of the sociology career was transformed several times.

Due to the rise of authoritarianism and the growth of military regimes in Latin America, during this period, academics and intellectuals were forced to leave their countries and many of them arrived at Mexico to teach at the Sociology Departments of the universities where they consolidated their work and influenced students and professors.

As a consequence of the military coup headed by General Pinochet, the Facultad Latino Americana de Ciencias Sociales (Latin American Advanced School for Social Sciences FLACSO) in Santiago, Chile, was forced to close and, in 1975, a branch was opened in Mexico.

The chapter analyses the main journals and publications of these periods, both the research results and the pedagogical textbooks, the studies of Mexican academics, as well as the authors from other countries that had an important impact in Mexico’s sociology.

Chapter 5 “From Particular Sociologies to Interdisiplinary Studies” addresses the important social and theoretical changes during the later part of the twentieth and the first decades of the twenty-first centuries.

As in other parts of the world, at the beginning of the 1980s, the end of the “orthodox consensus” (Giddens) sociology in Latin America was facing new theoretical and methodological challenges. Marxism and the theory of dependency lost the central role they had played in the teaching of sociology and other social sciences and sociology was influenced by postmodern debates, and criticisms to the “grand social narratives” and a search for other proposals.

The time period was also characterized by a new interpretation of the classics and a process of an increase specialization, with more focalized knowledge in specific fields like demographic studies, rural, urban, sociology, labour studies, historical and regional research, a growing interest on gender studies (1993); the search for new interpretative frameworks to understand nationalism, sovereignty, citizenship, globalization, and civil society; the influence of contemporary European authors, and a renewed attention to the study of new actors, social movements, identities, and subjectivities.

In line with the transformation of Mexico’s democratic institutions, one of the predominant themes of studies of the time were centred on the state, democracy, power, and the political system. In fact, during the 1980s and 1990s, the transition from authoritarianism was a focal point of Latin American social sciences, which explained the close relationship between sociology and political science at that time.

During this period, departments of sociology were established in various universities across the country, and new journals were created; there was an important increase in the number of women as students and academics of sociology. The government introduced new policies for financing and evaluating professors and researchers that shaped the procedures of academic world and influenced the field of social sciences in Mexican universities.

During the 1990s, the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the indigenous Zapatista Revolution in the state of Chiapas (1994) generated new sociological concerns.

The beginning of the new century showed that government policies in Mexico have not reduced social inequality and corruption. In addition, the country faced a growing wave of violence, and impunity in the face of organized crime. In face of this reality, sociology will focus on the study of the problems of violence, poverty, inequality, the exclusion of indigenous groups, and the growing importance of migrations.

To study the different causes of the national and international concerns, sociology abandoned the previous emphasis in specialization looking for interdisciplinary and more comprehensive research.

During the time, sociology in Mexico have similar interest to those of sociology worldwide, like the “cultural and affective turn” and the role of the growing interest on gender studies.

Sociologists intensify their various forms of participation in collective networks and Mexican sociology went through an internationalization process with an increasing number of publications in English, attendance at world forums, and collaboration with academics from other countries.

Given the content of this book, the author considers that it may be of interest not only for historian of sociology and social sciences but also for those interested in intellectual history, Latin American studies, social theory, relations between literature and social sciences, and other fields.

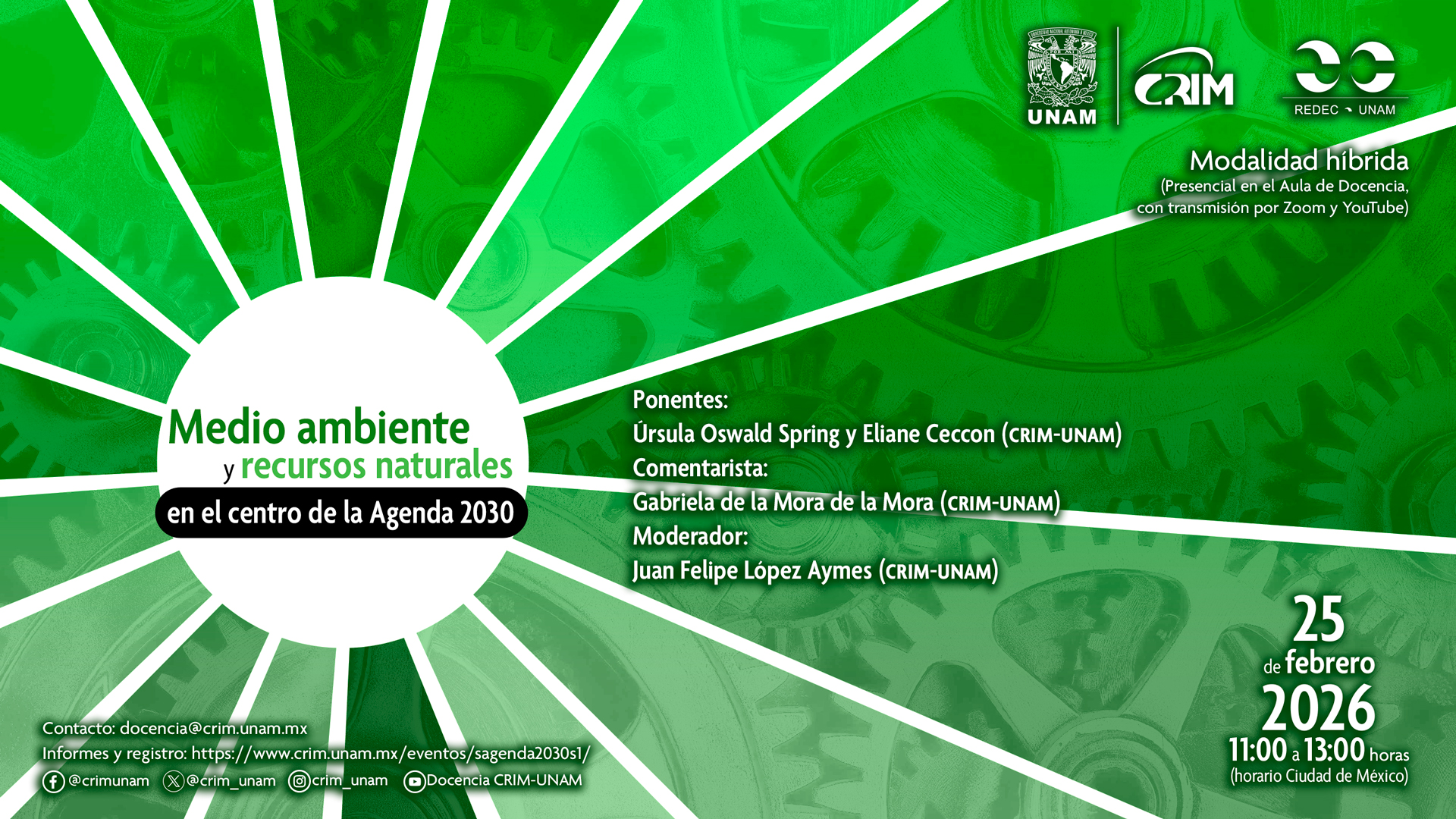

Te puede interesar

Convocatoria Feria del libro

Laura Gutiérrez - Feb 18, 2026FERIA DEL LIBRO X CONGRESO NACIONAL DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES “Las Ciencias Sociales frente a las incertidumbres actuales” INVITACIÓN Información general…

Hoteles con convenio | X Congreso Nacional de Ciencias Sociales

Laura Gutiérrez - Ene 28, 2026X Congreso Nacional de Ciencias Sociales Las Ciencias Sociales frente a las incertidumbres actuales del 23 al 27 de marzo…

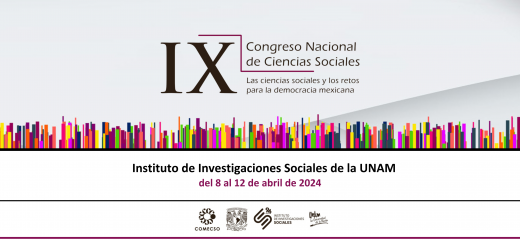

Memorias del IX Congreso Nacional de Ciencias Sociales

Roberto Holguín Carrillo - Jul 02, 2025IX Congreso Nacional de Ciencias Sociales Las ciencias sociales y los retos para la democracia mexicana. Realizado en el Instituto…

Problemas Estratégicos y Ciencia Social

comecso - Feb 18, 2026¡Nueva publicación, ineludible para quienes se desarrollan en el ámbito de las Ciencias Sociales! Nos complace anunciar la reciente publicación…

La sociedad rural mexicana en perspectiva

Laura Gutiérrez - Feb 18, 2026Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales y la Asociación Mexicana de Estudios Rurales, A.C. 14° Seminario de actualización…