Rethinking inside activism

Call for papers

Rethinking inside activism

Illiberalism, participation, and (un)mobilization

Avignon, June 19 and 20, 2025

Inside activism was the subject of a profusion of studies in the 1990s and 2000s, whether in the environmental field[1], gender politics[2], or urban policy[3], many of which can be found in the special issue devoted to it by Politix in 2005. Although this subject has received less attention since then, it has prompted much research abroad, particularly in Latin America. This event aims to revisit the study of institutional activism by examining it in the light of diverse political contexts, particularly within the authoritarian and illiberal dynamics that shape the commitment of public agents.

Power is a struggle field, shaped by competing and even contradictory dynamics. As early as the 1970s, Nicos Poulantzas shattered the myth of a monolithic state serving the interests of a single class. At the same time, specific reformist fractions within the Ministry of Public Works were funding urban struggles, such as that of the residents of the Alma- Gare district in Roubaix against the urban renewal project imposed by the municipality[4]. Militantisme institutionnel or inside activism can be defined as any proactive action by people occupying a position within a public bureaucracy to advance a specific “cause”[5]. The notion of institutional activism thus makes it possible to question and highlight the role of politicized civil servants or militant social workers without this commitment necessarily being linked to a structured collective organization. By providing funding, legitimizing actions, making premises available, and commissioning studies that can benefit mobilizations by legitimizing their demands, activists seek to influence political power relations. Gaps, divisions, and internal contradictions within the institutional world can provide opportunities for contentious action. Even within the police, despite a strong esprit de corps, there have always been weak spots and whistle-blowers. In his book on the March for Equality and Against Racism, Abdellali Hajjat gives the example of a police prefect who broke his corporative solidarity by publicly denouncing a CRS company guilty of violence against young people in a supermarket in Les Minguettes (Vénissieux)[6]. More recently, police lieutenant Éric Roman played a decisive role in denouncing racial profiling, passing on to the Défenseur des droits written orders from his superiors to “control all blacks and North Africans.” In other areas of public action, such as the fight against racial discrimination, creating an informal network of militant professionals has proved decisive in the timid advances made in this field since the 1990s. Marie-Christine Cerrato Debenedetti has clearly described how these civil servants, whether at central or local level, were able to contribute both to legitimizing the cause and to granting funding to specific associations mobilized around this issue before institutional reforms got to question the place of these inside activists[7].

Beyond the French context, in Latin America, institutional activism has developed remarkably in the context of the “participatory imperative”, where participation is thought to bring closer the populations further away from the political-administrative field, notably the working classes, and thus respond to the limits of representative democracy[8]. As a result, institutional activism raises the question of the ability of individual or collective actors involved in public institutions to advance the causes of the organizations they represent. More specifically, the aim is to observe how and to what extent the arrival in public administrations of actors who have previously had activist careers impacts the definition and implementation of public policies. Another question examines the consequences of such recruitments on the individual and collective careers of the activists involved[9]. Indeed, if “participatory democracy constitutes a repertoire of public and collective action[10],” it seems necessary to question how actors from the activist world seize this repertoire[11]. More recently, the arrival of illiberal governments, such as Bolsonaro’s in Brazil, or more explicitly authoritarian ones, such as Maduro’s in Venezuela, has triggered processes of deinstitutionalization of participation ranging from the reduction of public investment in participatory programs to the approval of laws that heavily constrain citizen participatory mechanisms[12]. In this context, institutional activism can be deployed as a form of resistance to face changes in public action imposed by the actors who dominate the political- administrative field[13]. It may also undergo destructuring or freezing dynamics, sometimes calling for professional reconversions by activists previously involved in public institutions[14].

This scientific event aims to examine institutional activism in light of illiberal dynamics affecting the exercise of institutional power. To unfold this question, we propose five research axes from which proposals can be inspired.

Axis 1. Localizing institutional activism. Socio-spatial and sectoral variations

The study of institutional activism is generally based on monographs or in-depth ethnographies. While these methodological approaches enable a detailed analysis of the processes and trajectories at play, we have less information on institutional activism’s socio- spatial, historical, and political variations. To what extent are specific sectors of public action conducive (or not) to deploying varied forms of institutional activism? Surveys on France’s “Politique de la ville” (urban policy), and thus on disadvantaged areas and social groups, shed light on a particular kind of activism emerging from situated relationships with social issues and discrimination. Do we find similar processes in other sectors, territories, or social groups? We might ask, for example, about the specific forms of institutional activism in the environmental, social, or cultural sectors. Do the variations have something to do with specific recruitment channels in each sector? Or specific professional cultures? If institutional activism has been studied mainly in sectors on the left hand of the state, what about the right hand and law enforcement officers’ engagement forms, for example? While the study of institutional activism has mainly focused on progressive forms of engagement, to what extent can we also document conservative forms of institutional activism? Comparative work is particularly welcome on this research axis.

Axis 2. Historical transformations in institutional activism

Studies of institutional activism, particularly in France, have focused heavily on the 1970s- 1980s, a period marked by a porosity between institutional and activist worlds much less present in other periods, especially in more recent ones. In Latin America, this research flourished during the 2000s, particularly by following the forms of institutional activism developed under the “pink tide” when a series of left-wing governments came to power. A diachronic approach to institutional activism can help us think about transformations in public action, such as the diversity of administrative practices, the evolution of the administrative field over time, and the effects of recruitment processes on the functioning of administrations, depending on the political systems or the public action sectors being observed. To what extent does the transformation of public action and its management shape institutional activism? Does institutional activism develops equally in less institutionalized public action sectors, where, for example, recruitment is less dependent on competitive selection? What about countries where the spoil system predominates and appointments are essential in selecting administrative staff?

Axis 3. Institutional activism and politics

This axis will focus on the relationship between public servants and politics in at least two ways. On the one hand, we’ll be taking a classic interest in the possible militant trajectories of agents by asking whether activism outside the institution is a condition for institutional activism or whether the latter constitutes rather a reconversion of activism first experienced elsewhere. We are particularly interested in union, association, and party membership, as well as the electoral behavior of institutional activists.

We’ll also look at the relationship with politics via the relationships between agents and elected representatives. To what extent does institutional activism presuppose privileged relations between agents and political representatives? To what extent can alliances with social movements help strengthen “weak” or peripheral institutions? Is there any circulation between agents towards more political positions, within cabinets or as elected officials? Conversely, does institutional activism sometimes work against those in power by building alliances between protesters and public officials?

Axis 4. Authoritarianism and institutional activism

A specific question will inspire this scientific event: to what extent do authoritarian or illiberal dynamics shape institutional activism? This question can be treated from at least two angles. Firstly, from an internal perspective, to what extent do authoritarian dynamics at a macro-political level impact the professional autonomy of public servants? To what extent is authoritarianism reflected in management practices and in the relationship between state or local agencies and civil society? From an external point of view, how do authoritarian dynamics – characterized in particular by a restriction of public freedoms and increased repression of mobilization and social criticism – make institutional activism more essential? Can institutional activism constitute a refuge for criticism coiled within the state when it struggles to express itself outside? To what extent can public servants act as whistle- blowers through their knowledge of institutional (dys)workings?

Axis 5. Conditions and effects of institutional activism

This section will examine the effects of institutional activism on the causes pursued, the movements that may be supported, and the agents involved. How do relationships between public agents and social movements influence each other (strengthening, weakening, autonomy, dependence)? What circulates between the two: funding? Information and knowledge? Strategic relationships? What are the social conditions of these circulations and alliances? To what extent can institutional activism shape the strategies and internal workings of social movement organizations? Can inside activism turn against mobilizations? We’ll also be looking at the effects of institutional activism on the public agents’ careers and on their capacity to develop their profession.

We invite paper proposals that fit into one or more of these axes. Proposals, in French or in English, should be no more than 5,000 characters in length and present the main question, the methodology, and the fieldwork being used. Comparative proposals that look at national contexts other than France or question the national or local specificities of institutional activism are particularly encouraged.

Send the proposals to the following mail addresses: yoletty.bracho@univ-avignon.fr; julien.talpin@univ-lille.fr

Calendar

- Response to the call: until January 17

- Replies from the scientific committee: end of January 2025

- Program publication: March 1, 2025

- Paper dispatch: May 9, 2025

- Symposium: June 19 – 20, 2025

Organizers

- Yoletty Bracho, Avignon Université – ·JPEG

- Julien Talpin, Université de Lille – CERAPS

Scientific Committee

- Amin Allal, Université de Lille – Ceraps

- Lorenzo Barrault – Stella, Université Paris 8 – CSU

- Claire Bénit, Aix-Marseille université – Mesopholis

- Jean-Louis Briquet, Université Paris 1 – Cessp

- Ouassim Hamzaoui, Avignon Université – ·JPEG

- Magali Nonjon, IEP d’Aix-en-Provence – Mesopholis

- Marie Hélène Sa Vilas Boas, Université Côte d’Azur – ERMES

- Jessica Sainty, Avignon Université – ·JPEG

- Carlos G. Torrealba M., Universidad Nacional de México (UNAM) – Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales (IIS)

- Gabriel Vommaro, Universidad Nacional de San Martín (UNSAM) – Conicet.

Descargar

[1] C. Spanou, Fonctionnaires et militants. L’administration et les nouveaux mouvements sociaux, Paris, L’Harmattan 1992.

[2] L. Bereni, A. Revillard, « Des quotas à la parité : “féminisme d’État” et représentation politique (1974-2007) », Genèses, n° 67, vol. 2, p. 5-23; A. Revillard, La cause des femmes dans l’État. Une comparaison France-Québec, Grenoble, Presses universitaires de Grenoble, 2016 ; A. G. Mazur, D. McBride Stetson (dir.), Comparative State Feminism, Londres, Sage, 1995.

[3] M. Nonjon, « Professionnels de la participation : savoir gérer son image militante », Politix, n° 70, vol. 2, 2005, p. 89-112 ; S. Tissot, « Reconversions dans la politique de la ville : l’engagement pour les “quartiers” », Politix, n° 70, vol. 2, 2005, p. 71-88.

[4] P. Cossart, J. Talpin, Lutte urbaine. Participation et démocratie d’interpellation à l’Alma-Gare, Vulaine-sur- Seine, Le Croquant, 2015.

[5] R. Abers, L. Tatagiba, « Institutional Activism: Mobilizing for Women’s Health from Inside the Brazilian Bureaucracy », in in F. M. Rossi, M. von Bülow (dir.), Social Movements in Latin America: New Theoretical Trends and Lessons from Mobilized Regions, Londres, Ashgate, 2014, p. 73‑120, p. 73 ; et plus récemment C. Bénit (dir.), Local officials and the struggle to transform cities, A view from post-apartheid South Africa, London, ULC Press, 2024.

[6] A. Hajjat, La Marche pour l’égalité et contre le racisme, Paris, Amsterdam, 2013. Plus largement, voir A. Delfini, J. Talpin, J. Vulbeau (dir.) Démobiliser les quartiers. Enquêtes sur les pratiques de gouvernement en milieu populaire, Villeneuve d’Ascq, Presses universitaires du septentrion, 2021.

[7] M.-C. Cerratto de Benedetti, La lutte contre les discriminations ethno-raciales en France. De l’annonce à l’esquive (1998-2016), Rennes, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2018.

[8] M.-H. Bacqué, H. Rey, Y. Sintomer, Gestion de proximité et démocratie participative : une perspective comparative, Paris, La Découverte, 2004.

[9] L. Barrault-Stella, A. Maillet, G. Vomaro, « Étudier les transformations de l’action publique en Amérique latine.

[10] M.-H. Sa Vilas Boas, Du quartier à l’État : sociologie des publics des dispositifs participatifs brésiliens, Université d’Aix-Marseille, 2012, p. 34.

[11] L. Perelmiter, Burocracia plebeya: la trastienda de la asistencia social en el Estado argentino, San Martín, Universidad Nacional de San Martín, 2016.

[12] C. De Paiva Bezerra, D. Rezende de Almeida, A. Durza Lavalle, M. W. Dowbor, « Desinstitucionalização e resiliência dos conselhos no governo Bolsonaro », SciELO Preprints, 2022.

[13] C. Tomazini, « Une conjoncture critique pour les politiques sociales au Brésil ? L’ère post-PT et le gouvernement Temer (2016-2018 », in F. Andréani, Y. Bracho, L. Laplace, T. Posado (dir.), Alternances critiques critiques et dominations ordinaires en Amérique latine. Crises, résistances et continuités, Rennes, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2024.

[14] Y. Bracho, « Militer dans l’Etat : sociologie des intermédiations militantes de l’action publique au sein des classes populaires à Caracas (Venezuela) », Lyon, Université Lumière Lyon 2, 2022.

Te puede interesar

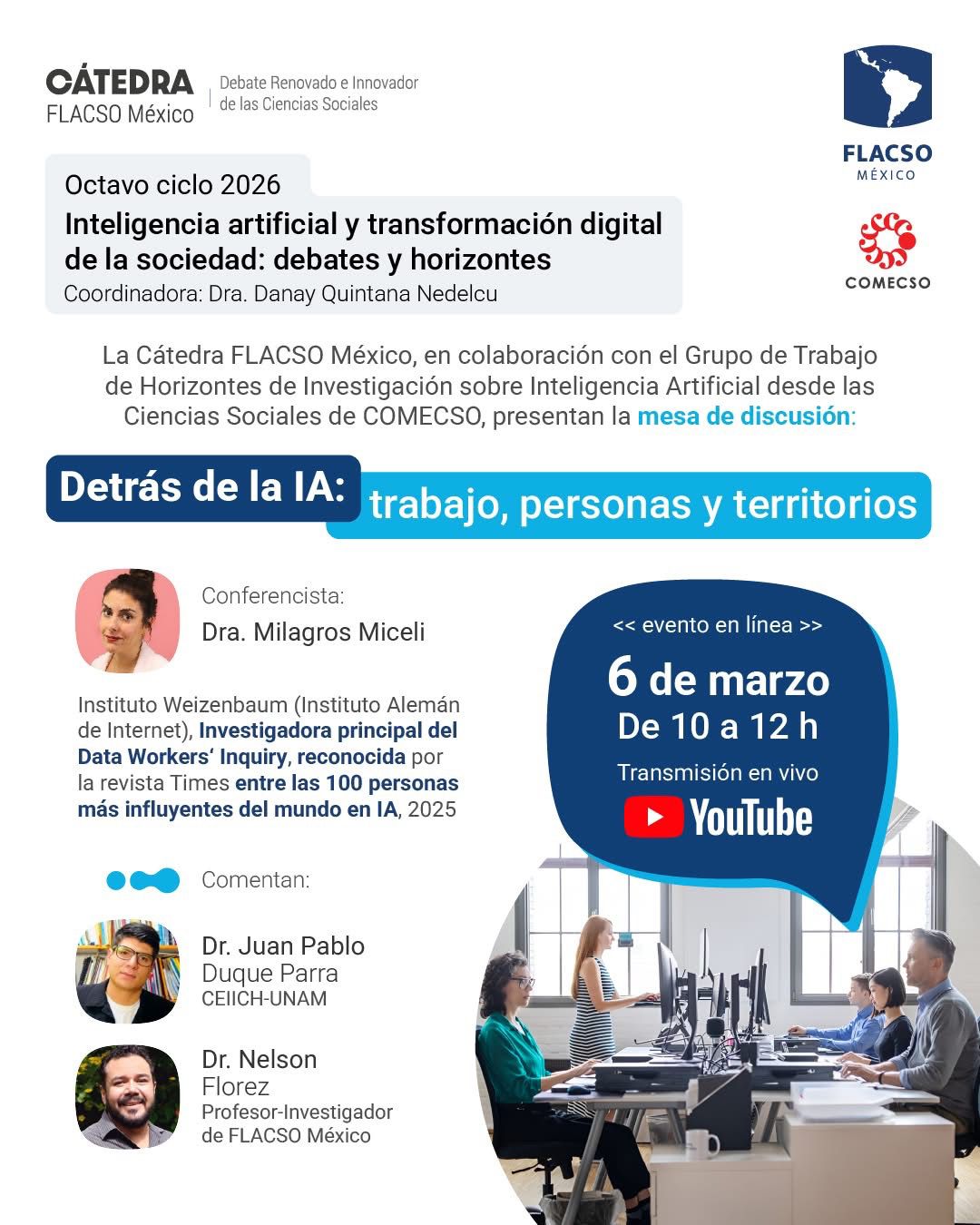

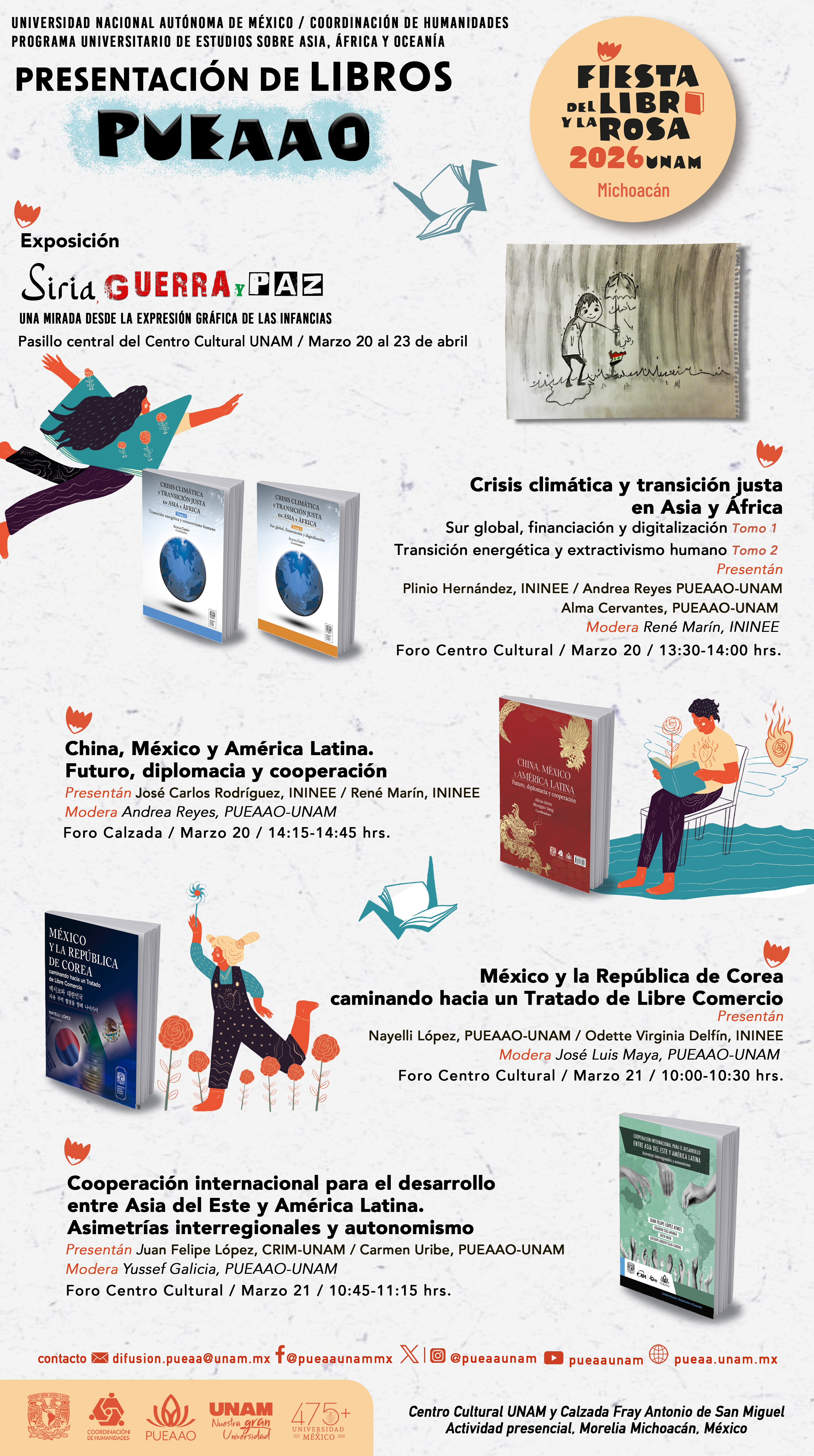

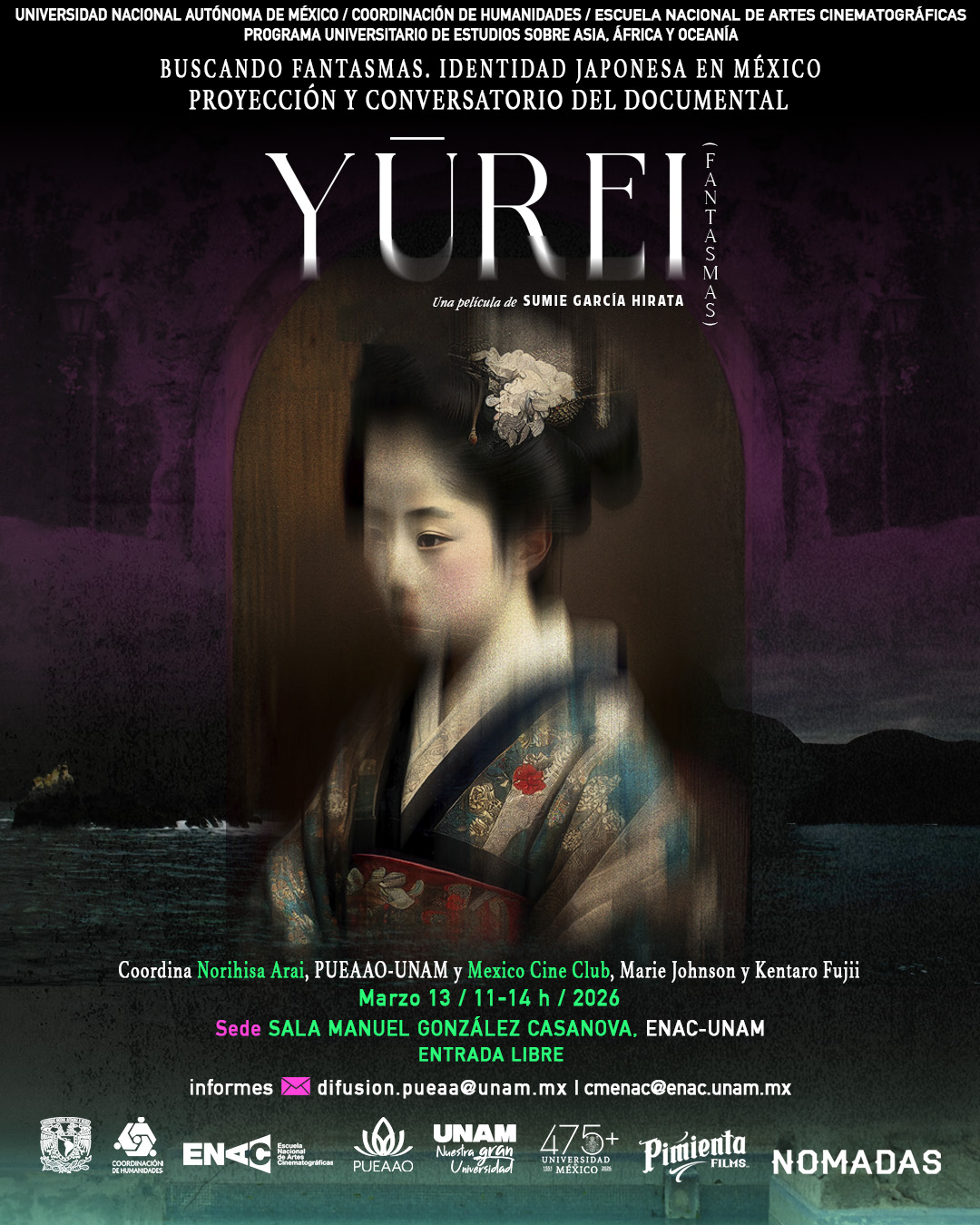

Programa del X Congreso Nacional de Ciencias Sociales

comecso - Mar 11, 202623 al 27 de marzo, 2026 | Posgrado de la Facultad de Contaduría y Administración, Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua, Campus…

Hoteles con convenio | X Congreso Nacional de Ciencias Sociales

Laura Gutiérrez - Feb 25, 2026X Congreso Nacional de Ciencias Sociales Las Ciencias Sociales frente a las incertidumbres actuales del 23 al 27 de marzo…

Memorias del IX Congreso Nacional de Ciencias Sociales

Roberto Holguín Carrillo - Jul 02, 2025IX Congreso Nacional de Ciencias Sociales Las ciencias sociales y los retos para la democracia mexicana. Realizado en el Instituto…

Doctorado en Gestión de la Educación Superior

Laura Gutiérrez - Mar 11, 2026Universidad de Guadalajara, Centro Universitario de Ciencias Económico Administrativas Doctorado en Gestión de la Educación Superior Convocatoria 2026-B DIRIGIDO A…